Ok, but what actually is autism?

An introduction to autism (by a real-life autistic)

Autism.

Almost everyone has heard of it, probably mentioned it in conversations, and has some subconscious conjecture about what it means.

But how many of us actually know what autism is?

Within the human species, there is a wide diversity of neurocognitive styles (types of minds). Autism is a term to describe one such neurological variant. Most people have a neurocognitive style that could be described as neurotypical, with those whose neurology differs significantly from this dominant type being referred to as neurodivergent (because they ‘diverge’ from the dominant type). Autism is one of many forms of neurodivergence, and one that is fundamental to the autistic individual’s personhood - you can’t separate the person and the autism (physically or conceptually) because the person is autistic. In a vacuum, being autistic is no better or worse than being neurotypical. Both are just neutrally different ways of thinking, feeling, moving, communicating and overall experiencing the world. Autism is not a disorder, a mental illness or an inherent deficit - it is simply a neutral neurological difference.

Scientists don’t yet know for sure how autism arises, but there’s compelling evidence that it begins in the womb, with genetic components being largely involved. It’s thought that autism can arise via multiple different pathways and with the involvement of different gene combinations. Instead of being one unitary neurological variant, autism might be a collection of multiple highly interrelated neurological variants, which could further explain the wide phenotypic variability. An autistic person is born autistic and remains as such throughout their entire life. An allistic (non-autistic) person cannot suddenly become autistic and an autistic person cannot suddenly become allistic.

It’s a common misconception that autism is an intellectual disability. Some autistics have intellectual disabilities, but autism itself isn’t an intellectual disability. Similarly, some people assume that all autistics are geniuses or savants, or have some sort of special talent. This is true for some autistics, but not all, or even most.

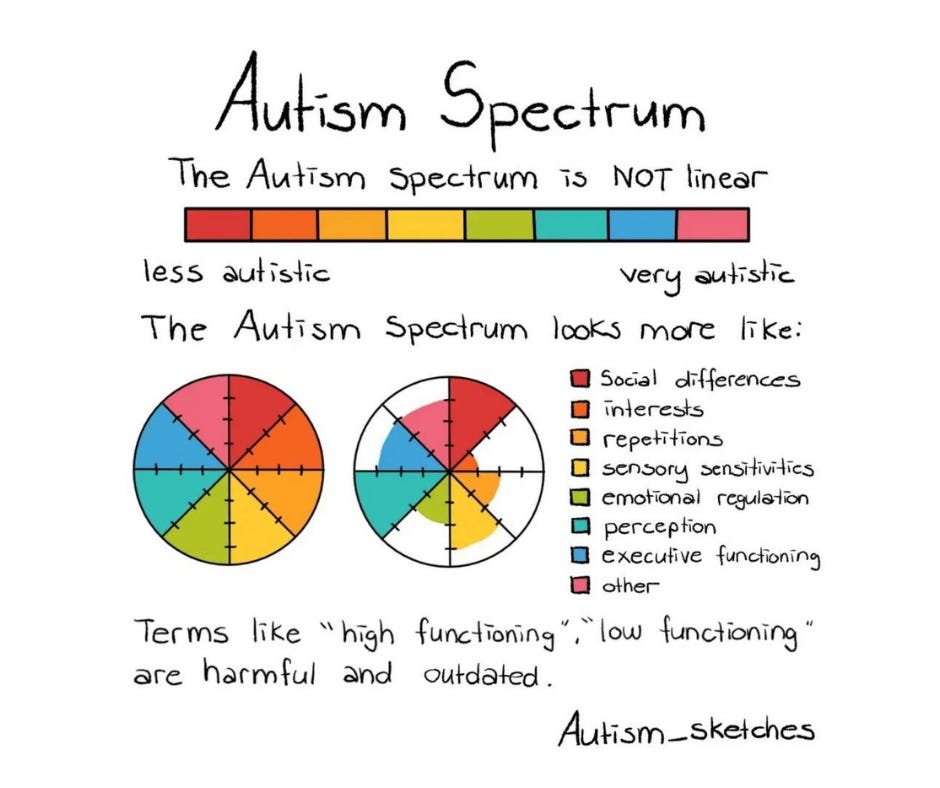

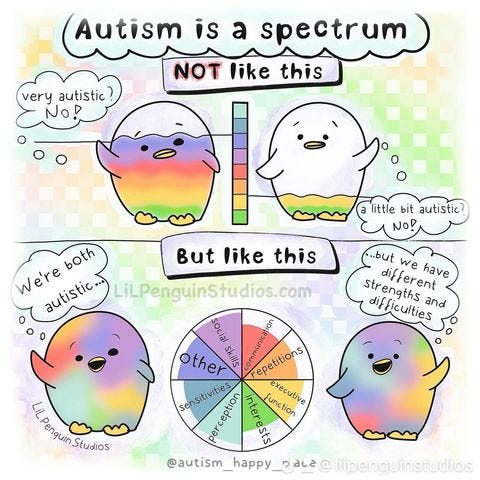

It is important to acknowledge autism as a *spectrum* - this refers to the vast variation in how autism affects or manifests in different autistic individuals, despite notable similarities in their neurocognitive styles. Not every ‘autistic trait’ or example I provide will be applicable to every autistic person. We all have different personalities, interests, likes and dislikes, skill sets, struggles, support needs, circumstances, intersecting identities, etc, and such a wide range of experiences makes it hard to generalise among the entire autistic population.

I want to emphasise that spectrum does not mean a scale of severity - there is no such thing as ‘mild’ or ‘severe’ autism.

Overall, autistics tend to experience more *intensely* than neurotypicals. In her book ‘Neuroqueer Heresies’, Dr. Nick Walker writes; ‘The complex set of interrelated characteristics that distinguish autistic neurology from non-autistic neurology is not yet fully understood, but current evidence indicates that the central distinction is that autistic brains are characterized by particularly high levels of synaptic connectivity and responsiveness. This tends to make the autistic individual’s subjective experience more intense and chaotic than that of non-autistic individuals: on both the sensorimotor and cognitive levels, the autistic mind tends to register more information, and the impact of each bit of information tends to be both stronger and less predictable.’

A more intense experience has both upsides and downsides. As a personal example, unwanted unexpected touch, such as strangers patting or squeezing my arm, causes severe prolonged discomfort; it’s not painful as such but I can feel a distinct imprint where their hand was, the sickly unshifting sensation echoing its horror for minutes or even a few hours after. The person likely didn’t intend harm, but I can’t help feeling violated, and that my autonomy and boundaries have been undermined. While lots of neurotypicals would find such unwanted touch at least a bit invasive, most wouldn’t have such a potent and extended reaction. On the positive side, a consensual long tight hug from someone I love and trust provides immense comfort, both physically and emotionally. The deep pressure seeps right down through my skin, down to my muscles and into my bones (in a nice way!!), with its reverberation encompassing my body well after arms have been unclasped. Autistic joy is a wonderful thing.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Because mental and physical processes are often interconnected, autistics can share some similar behaviours. For instance, many autistics:

get overwhelmed by sensory stimuli such as lights, noises, smells, touch, etc, that neurotypicals tend to not take much notice of;

experience meltdowns and/or shutdowns due to sensory and/or emotional overwhelm;

take longer to process information when compared to most neurotypicals;

are extra attentive to detail;

rely on routines, structure and planning more than most neurotypicals, and experience much more anxiety in unpredictable and unfamiliar situations;

stim (self-stimulatory activities that tend to involve repetitive, predictable patterns). Examples include hand flapping, rocking, chewing gum, humming, playing with fidget toys, spinning, skin-rubbing/scratching, repeatedly feeling a particular texture, watching a moving object like a lava lamp, among an infinite list of others.

are very knowledgeable about certain subjects/activities that they have a particularly keen interest in, and often like to share with others;

have differences in communication. Examples include avoiding eye contact, non-speakers using AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication), disliking and/or avoiding small talk, internal emotions sometimes not being very obviously externally displayed when compared to most neurotypicals, such as not smiling to the expected extent when we’re happy (when not masking and forcing a more ‘appropriate’ smile) or perhaps not laughing in response to something we find genuinely funny, asking for clarity when something is ambiguous, finding it difficult to converse in noisy environments or when there are other sensory disruptors such as flickering lights, and so on. Such differences often lead to us being misinterpreted which in turn leads to many of us developing social anxiety. Being socially anxious isn’t an innate ‘autism thing’, but many autistics develop it from a young age due to being misperceived and condemned for their communication differences, and more generally, just for being autistic - it is a symptom of our oppression-induced trauma rather than a problem with our innate neurology. I recommend exploring the theory of the ‘Double Empathy Problem’ which further details barriers in communication that can occur between autistics and allistics.

Autism is considered a disability because, as is the case with many disabilities, our society is largely created without us in mind; it is designed around the needs of neurotypicals, with autistics and many other neurodivergent individuals being expected to just deal with it all. In a vacuum, being autistic is no better or worse than being allistic, but cultural attitudes and lack of reasonable accommodations lead to our oppression and marginalisation. In turn, many autistics are limited from reaching their potential over a range of contexts. There is a disproportionate risk of mental illnesses and suicide among the autistic population. These are of course complex matters which tend to arise from multiple intertwining factors, but it would be reasonable to expect autistic mistreatment, which manifests in a myriad of ways, to be a significant contributor.

I want to stress that this isn’t a case of people with victim mentalities avoiding accountability by using ‘society’ as a scapegoat - autistics genuinely aren’t the problem. We aren’t asking for all that much - respect, acceptance, autonomy, inclusion… The accommodations we need really aren’t big inconveniences (in fact, embracing neurodiversity benefits everyone), but could prevent an enormous amount of suffering and death.

Here are some additional resources for autistics and allistics alike: